Open House Spatter

- Jade Yumang

-Galleries I & II-

Open House Spatter

Private Parts

In step with the emergence of an emphasis on individualism in modernity’s lurch toward the neo-liberal politic with which we presently struggle in pursuit of states of social and ecological justice, there is a paradigm comprising an artwork’s authorship, a point of view from which production issues, and an apparatus of power relations by which this unique being is interpellated, subjugated, latently identified, or otherwise produced as a consequence of hegemonic power. Across the past two hundred years, the significance of an artist in the interpretation of their work looms ever larger for most creative fields; one notable lag in this development is the appreciation of the labor behind many textile arts, forms of handiwork, and artistic practices associated with the domestic—for our purposes, that slight deviation that has long been critiqued for subordinating the creative activities of women may in fact prove useful in mounting a resistance to a compulsory subsumption of art into capital.

Condensed around this individual artist-author is the marked threshold between the solitude of the space of production, i.e., the studio, and a thereafter conditioned by discourse, crisscrossing gazes, and consumption, in other words, the gallery. Built into the work of any artist then is to devise a self-conscious methodology by which one’s work moves from interior to exterior, and in so doing, each maker confronts a responsibility to test the veracity of the long-reified notion of privacy.

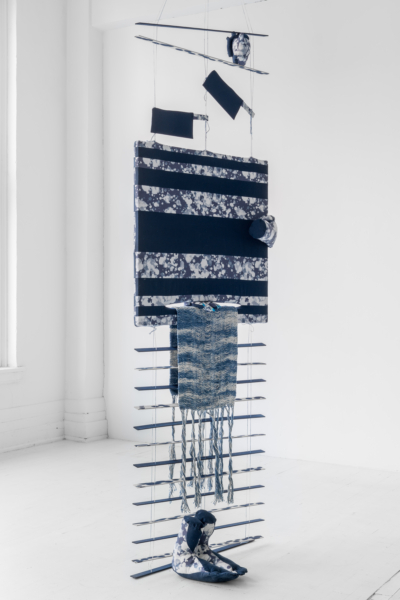

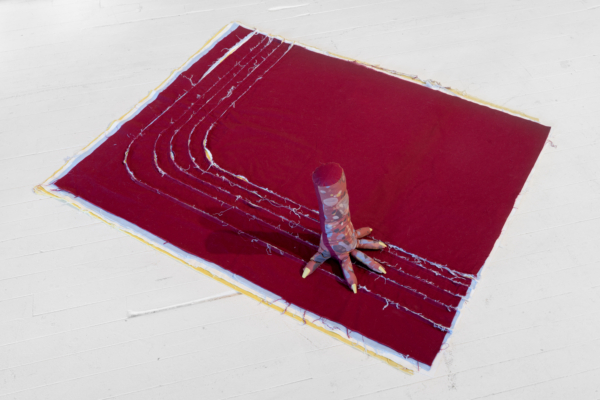

The private sphere warrants scrutinizing. In his mélange of sewing, interior decoration, printmaking, and a panoply of the so-called ‘domestic arts,’ Jade Yumang develops a vantage from which the effects of capitalism’s particular forms of privatization undergo a queer/ed analysis. The premise of privacy has long served to shield all sorts of oppressions that too often proceed without intervention or even recognition: domestic abuse, the repression of nonnormative sexual practices, and an exclusionary economics by which upper tier wealth is consolidated are but a few examples of harm hiding out in the interior corners of the private. For that matter, we might recall that the earliest written laws that dictated the ownership of private property applied to women and children as slaves in Rome. Yumang’s assemblages go some distance to insist on remembering the embodied stakes that are navigated behind closed curtains, closed blinds, closed doors, closed closet doors. Citing the exercises in control and being controlled that characterize the homemaker, Yumang aggregates tropes of domestic space into disoriented fragments. Ruffled curtains and other affected window treatments, woven rugs and blankets, and quoted wallpaper and flooring designs have been assembled into psychologically fraught scenery. In particular, Yumang positions the “gay spatter” patterning of popular mid-century vinyl floor tiles as a kind of presentiment for a range of unspeakable violences—physical, psychical, symbolic—seeping out of the contours of heteronormativity and its pressures to assimilate.

The home as Yumang references it is a complex concept that emerges from the onset of the Industrial Revolution when the homemade was supplanted by the mass produced, and with it, the necessity of the nuclear family as a self-contained workforce was eroded. Migrations into growing metropolises and the proliferation of claims to non-reproductive sexualities were among the side effects of these substantive shifts precipitated by new technological means of manufacturing and the widespread implementation of a capitalist certainty that everything can be assigned a value for exchange. Circulation ousts the cohesion of a tribal sense of connectedness in a dawning globalized cultural economy. While history bears witness to several generations of vibrant demonstrations by workers, thinkers, artists, and students who propose ways this new order might be developed into a socialist commons, the mostly unregulated might of private interest has taken hold of the developed world and its resources. The logic of the individual is co-opted in neo-liberalism whereby corporate entities have been afforded the same rights and status. Most any romantic notion of autonomy has slidden into a form of alienation so violating that bodies come apart from themselves—under fire of drones, in the disruption of sexual and reproductive rights, and from the non-consensual export of our tendencies as data.

The pleasing palettes and neat craftsmanship of Yumang’s soft sculptural projects initially camouflage all the dismemberment scattered throughout these pieces. Hands, feet, and internal organs are torn asunder, composed from decorative textiles that coordinate with the knives, axes, and other weaponry that punctuate this bodily disarray. An unlikely fusion of slasher film rampage and functionally obsolete daydream of middle-class aspirations presages Yumang’s figuration of the queer as deviant interlocutor—by different strokes pervy, paranoid, homebody, and hysteric.

In terms of precedent, one might look to Judith Anderson’s turn as Mrs. Danvers in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 thriller Rebecca, the housekeeper remnant of a home made by the lord of the manor’s first wife for whom Danvers continues to harbor fanatical, libidinous adoration years beyond her death—so much so that she would sooner set the house ablaze than allow for a private life without the woman to whom she was devoted. Or elsewhere consider the disembodied hand Thing T. Thing who consistently appears in default servant roles in the various television and film iterations of The Addams Family, based on cartoons developed by Charles Addams. As with Mrs. Danvers, Thing operates within but separate from the family unit. Both constantly signal their exteriority. And it is to this exteriority that Yumang’s slices of murder mansions propose we aspire.

What emerges out of these ruins of private domiciles wrecked by queer desire in revolt? What next world is glimpsed between the slats of Venetian blinds in this or that of Yumang’s tableau? Perhaps looking to the quasi-communism of Larry Mitchell’s Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions or the militant collectivism modeled by the women in Monique Wittig’s Les Guérillères would provide a template for a public inclusive of desires, sexualities, and expressions heretofore repressed or rendered fugitive. The crux, it would seem, is a capacity for mutual care, even in mutilated partialness. Décor then exists as a politics of the anticipatory: an a priori place-making predicated not on the opacity and alienation of the private, but rather on a coalition of differences committed to the needs of the many.

Matt Morris

Author Biography

Matt Morris is an artist, writer, perfumer, educator, and curator based in Chicago. Morris has presented artwork nationally and internationally. He is a contributor to Artforum.com, Flash Art, Fragrantica, The Seen and X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly, and other publications; and other writing projects appear in numerous exhibition catalogues and artist monographs. Morris serves as an Assistant Adjunct Professor in Painting and Drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Artist Biography

Jade Yumang examines how queer optics permeate into culture, how that is absorbed, embodied, repeated, and eventually materialized into deviating forms through a variety of techniques to convey notions of phenomenology, affect, and “queer” as a process. Jade received an MFA at Parsons School of Design with Departmental Honors in 2012, and a BFA Honors in University of British Columbia in 2008. Selected exhibitions include: Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn, NY), John Michael Kohler Arts Center (Sheboygan, WI), Museum of Arts and Design (New York, NY), Art League (Houston, TX), TRUCK Contemporary Art (Calgary, AB), Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art (Overland Park, KS), Des Moines Art Center (Des Moines, IA), Western Exhibitions (Chicago, IL), BronxArtSpace (Bronx, NY), The Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art (New York, NY), District of Columbia Arts Center (Washington, DC), Glasshouse (Brooklyn, NY), and ONE Archives (Los Angeles, CA). Jade is the recipient of several grants from Canada Council for the Arts and British Columbia Arts Council; and is featured in the book Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community. Jade was born in Quezon City, Philippines, grew up in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, immigrated to unceded Coast Salish territories in Vancouver, BC, Canada, and currently lives in Chicago, IL, USA, which sits on the traditional homelands of the people of the Council of Three Fires, the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa as well as the Menominee, Miami and Ho-Chunk nations. Jade is part of a New York-based collaborative duo, Tatlo, with Sara Jimenez and is an Assistant Professor in the department of Fiber and Material Studies at School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Video credit I : Jade Yumang

Video credit II : Samuel Alie

Photo credit : Jean-Michael Seminaro